Louis Wain was born in London on August 5th, 1860, to an upper class family and grew up right in the middle period of the Victorian era. He was the eldest child and only son with 5 sisters. His mother was of French descent and his English father was a textile trader and embroiderer who owned Church Fabrics. At it’s peak, the business employed 12 staff and the family lived on Brook Street in Mayfair with 3 house servants.

Louis was born with a cleft lip and doctors at the time advised that he be kept at home until he was ten. When he was eventually enrolled in school, his academic performance was considered average at best. Although poor in most of the sciences, he excelled in music and sports. His artistic personality was already emerging, and he further self-nurtured towards that direction by often playing truant from school and spending most of his time wandering around London. These jaunts would provide the sights and inspiration that would influence his work throughout his later life.

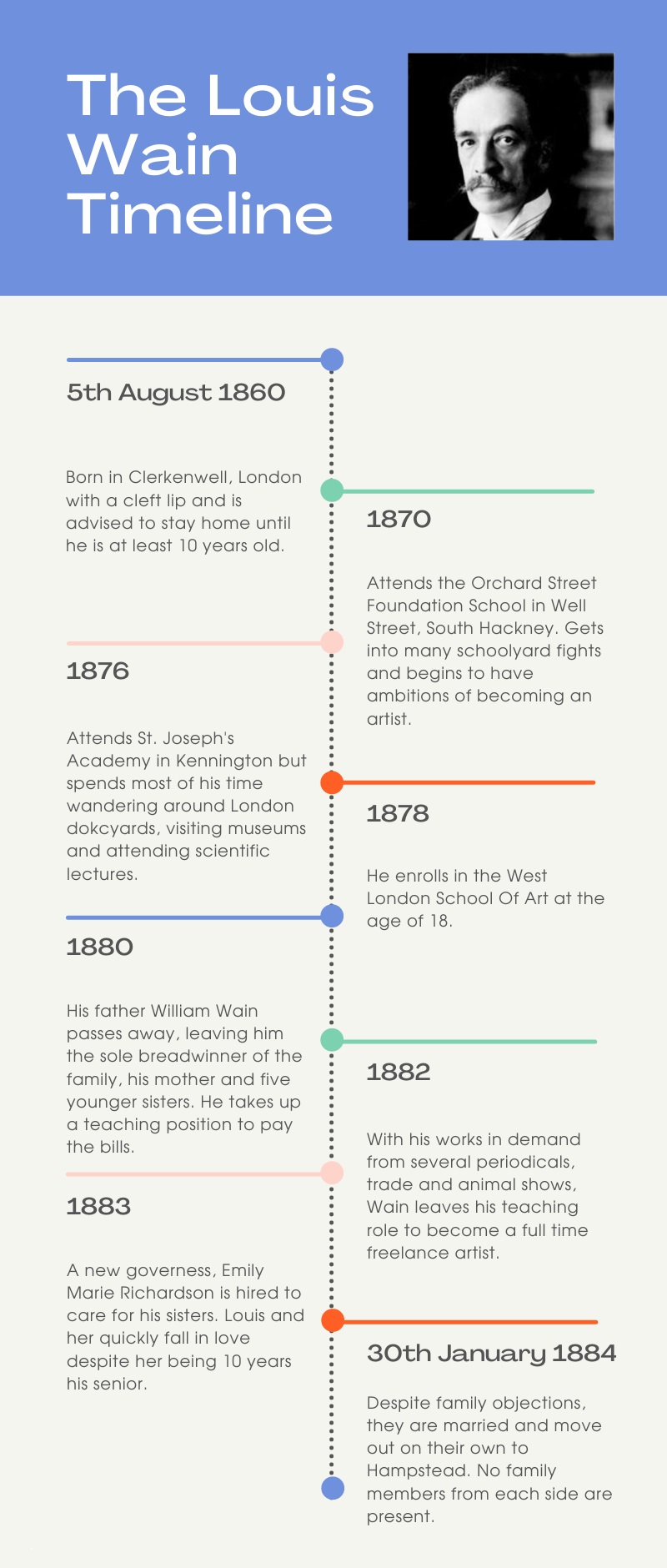

It wasn’t long after that he studied at the West London School Of Art (which was a relatively new institution at the time) and subsequently became a teacher there. Around this time, the first tragedy struck. His father, William Matthew Wain passed away when he was 20 years old and his mother went bankrupt when she tried to sustain the family business. This put Louis as the man of the family and the main breadwinner; he took on those responsibilities admirably.

First he left his full-time position to become a freelance artist who specialized in drawing animals and country scenes. His work was commissioned by periodicals like the Illustrated London News and the Illustrated Sporting & Dramatic News. Louis was also in demand to draw animal portraits for the many circuses, agricultural and livestock trade shows around London. Throughout the 1880s, Wain’s work included detailed illustrations of English country houses and estates but his fame grew as the artist who could draw any type of creature or animal.

Although a natural lefty, he was ambidextrous and could perform tricks like mirror writing (which led to speculation about his symmetrical works in later life). Louis could draw incredibly quickly. At times he could draw up to 150 cats with an average of a single cat in under 30 seconds. He was proficient in watercolor, oil based paints, crayons and even silver point, a medieval method of drawing by scratching surfaces with silver wire.

When he was 23 a new governess by the name of Emily Richardson was hired to take care of his sisters. Although she was 10 years Louis’s senior, they got married and moved to Belsize Park in Camden. Although the age difference was considered taboo at the time, it did not bother them as they were very much in love and supportive of each other. However as a result they were estranged from Louis’s family, whom did not approve of their union.

Sadly, the second tragedy struck less than 3 years into their marriage when Emily was diagnosed with an inoperable breast cancer. Louis spent much of his time with with her and together they rescued a stray black and white kitten who got their attention by making noises at night. Naming him Peter, the male kitten comforted Emily during her illness, and Louis started drawing extensive sketches of him.

In no time, their home had Peter’s portraits hung up on clotheslines everywhere and were a delight to all their visitors. Emily strongly encouraged him to have those pictures published, and without knowing it, had helped Louis onto the path of drawing the very animal that would define his entire life and career.

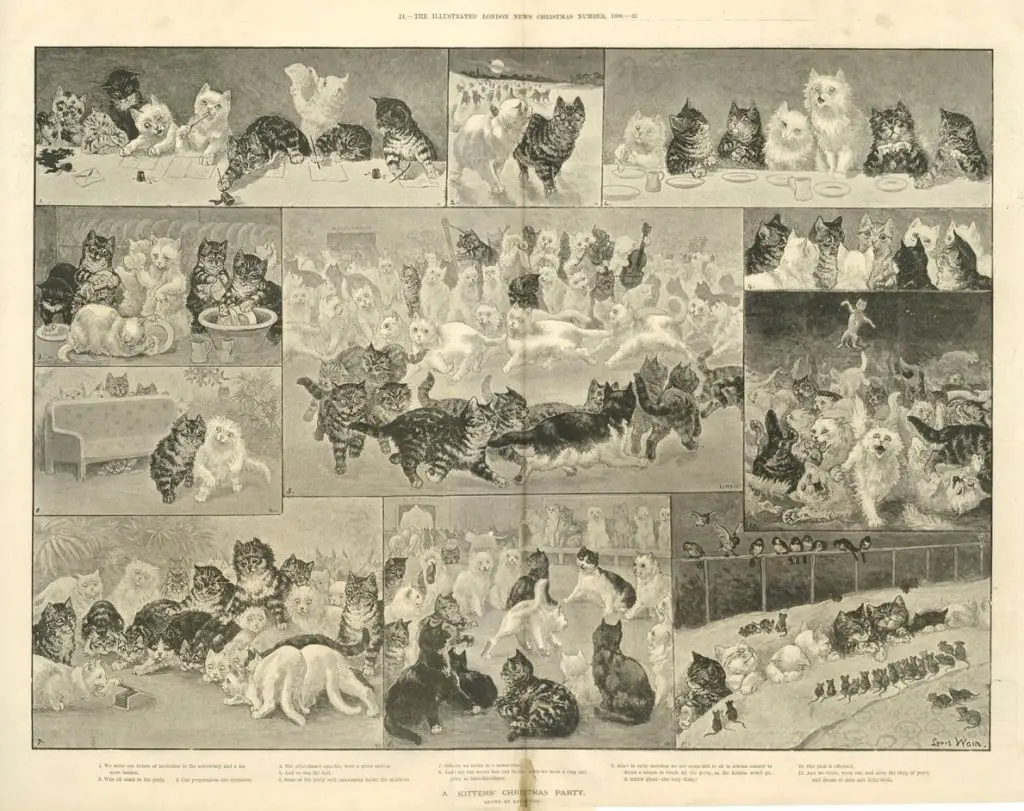

In December 1886 he had persuaded William Ingram (then editor of Illustrated London News) to publish his centerfold double spread ‘Kittens Christmas Party’ (image shown above). This single illustration would turn him into a household name and ensure that he had commission work for the rest of his life. Not many knew at the time that Peter the cat was in the illustration as well. It was a stroke of good fortune for them and Emily was happy for Louis.

The old saying ‘when one door closes, another opens’ sadly comes to mind. A week later, on January 2nd, 1887, Emily Wain passed away, leaving Louis behind at the age of 26. For the rest of his life he never stopped drawing cats, perhaps in order to maintain a lifetime connection to his memories of Peter and Emily.

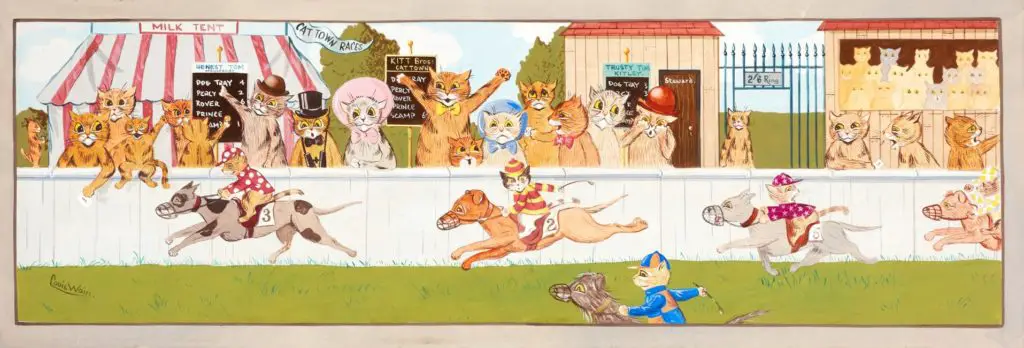

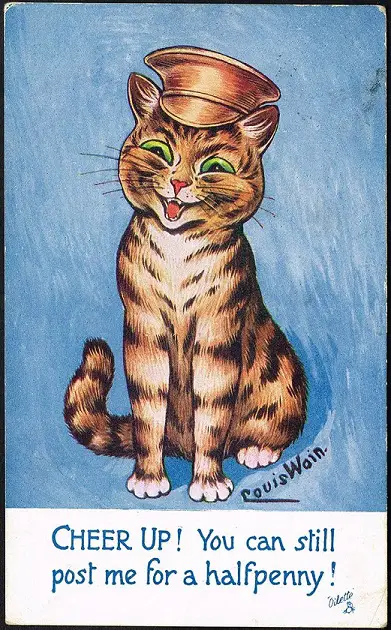

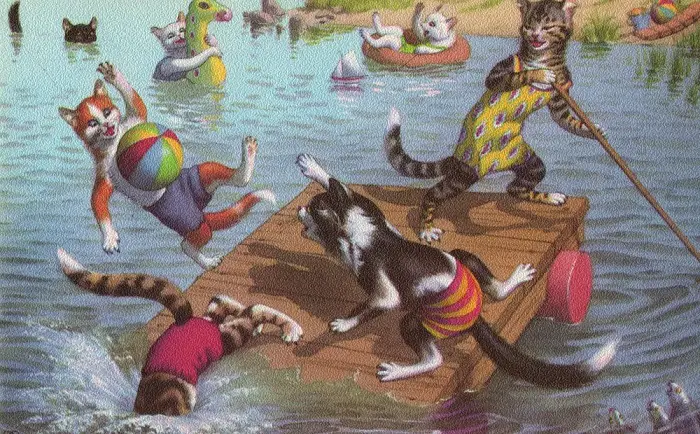

In subsequent years, his art style would evolve and start to feature anthropomorphic cats that would wear human clothes and partake in activities such as golf, drinking tea and playing musical instruments which coincided with the Victorian ‘age of leisure’. He was still extremely prolific, dedicating his energy into several hundred drawings per year as his work continued to be featured in major newspapers, journals and magazines. No wonder that the early 1900s saw the rising popularity of the humble postcard, which Louis’s drawings no doubt contributed to. All in all, over 100 publishers put out more than 1,100 unique postcards featuring his works. Today, the originals are highly sought after collector’s items.

During this time he also drew many illustrations for a series of children’s books by Clifton Bingham under the pseudonym George Henri Thompson.

With the help of Amphora ceramics in 1914, Louis Wain designed a series of cubist style sculptures of cats and dogs, that represented his artistic expression in the genre. These were considered ugly at the time and were poorly received as compared to his artwork. Despite being a financial loss back then, today we can see that Louis was ahead of his time. These figurines easily fetch 5 figures (even in Sterling Pounds) on the current auction market.

Even throughout his busy schedule, he found the time to lend his hand to several animal charity groups such as Governing Council of Our Dumb Friends League, the Society for the Protection of Cats, and the Anti-Vivisection Society. He was also acting Chairman and President of the National Cat Club, helping to dispel negative notions of cats in England that brewed during the medieval period. He also ended up adopting many other stray cats, who were less famous than Peter because he had less time for them individually. Visitors to his home were often surprised to see that Louis kept several pet dogs as well,

While he was a very modest and kind person, he was also a poor negotiator and too trusting in publishing and business, often getting scammed into making bad business investments and giving up the rights for his artwork for small fees with no ongoing royalty compensation. Despite being a commercially successful household name, these factors coupled with supporting his mother and five sisters meant that his financial situation was always precarious.

As the years went by, Louis suffered from a decline in mental health. It may have run in his family genes as his younger sister Marie was committed to an insane asylum in 1900. The tragedies continued. His sister Caroline also died in 1917, and Louis started to blame his living sisters for her death. Over the next seven years he became increasingly hostile and violent towards them. He also became extremely paranoid and displayed obsessive compulsive behaviors.

When his sisters could no longer cope with this, they called the doctor and in 1924, Wain was committed to a pauper ward of Springfield Mental Hospital. His family could not afford better care; they even had to visit him to collect his artwork which they would sell to pay the bills. A year later, he was discovered there, and his circumstances led to appeals from the sci-fi author H. G. Wells and the personal intervention of then Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin. The appeals collected twice the amount of donations requested, a huge success. As a result, he was transferred to the Bethlem Royal Hospital in Southwark, and again in 1930 to Napsbury Hospital to receive a better standard of care.

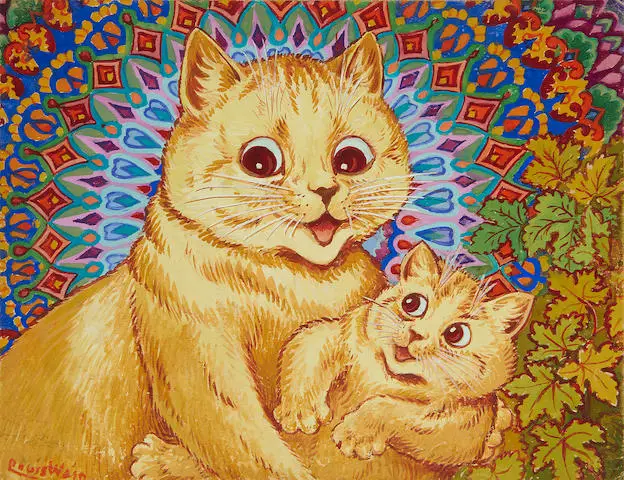

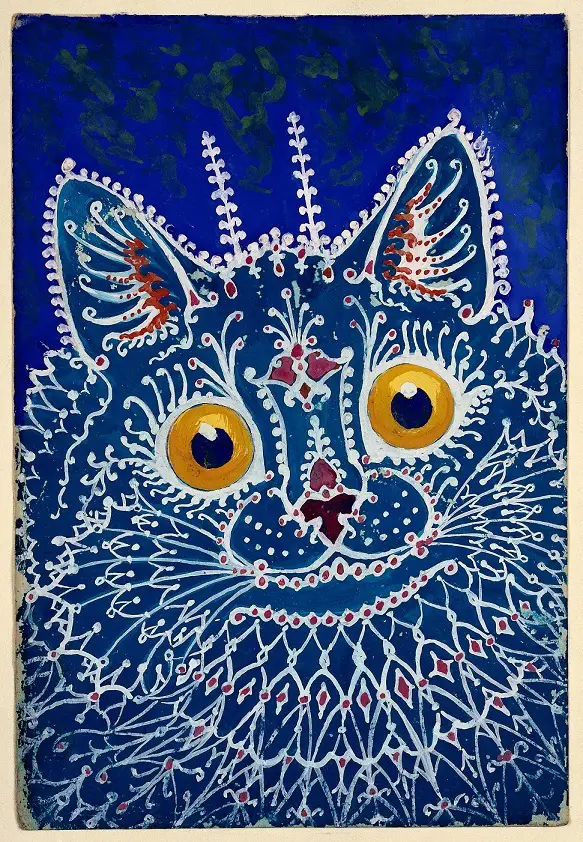

The move was good for Louis. Napsbury was idyll and beautiful, and he was always accompanied by a garden colony of cats. Freed from the stress of his commercial obligations, it was here that he created most of his iconic work, marked by bright colors, flowers, and intricate and abstract patterns. It is very likely that Louis was influenced by his childhood where he was surrounded by tapestries and wallpaper designs from his father’s business. During Christmas he would paint cartoon cats on mirrors throughout the home, bringing good cheer to his fellow inmates.

There is some irony that a cat artist was saved by crowdfunding almost a century ago, but it really was the public’s affection for Louis that gave him another lease on life.

And so it was here that Louis Wain finally found peace and tranquility in his final 15 years. On the 4th of July 1939, at the age of 78, he was buried together with his father and two sisters in Kensal Green. In a modern age, filled with an abundance of cat memes and artists, we should all know the tragic life story and pay tribute to the one who started it all.

Speaking of paying tribute, none other than Benedict Cumberbatch will play Louis Wain in the upcoming eponymous film biopic which is directed by Will Sharpe. This will definitely revive interest in the man and his artworks, probably driving up the prices as well. Let’s keep our paws crossed that the script and directing will do justice to this incredible story.

Note: There has been a lot of speculation that he suffered from bipolar disorder or schizophrenia due to contracting toxoplasma gondii, a parasite known to be carried and excreted by cats. Some psychiatrists point to his deteriorating mental health manifesting in later and admittedly more psychedelic paintings and drawings. Most of these claims have since been debunked. Furthermore, author Rodney Dale proved that Louis was still drawing his regular cartoon cats at the same time he was making the psychedelic ones. From accounts of people who knew him, it is more likely that he had Asperger’s syndrome, a high-functioning type of autism, whose sufferers frequently exhibit genius like skills.

Check out this excellent article from Simon Hitchman here which gives a detailed account of his life and is full of great images.

The best book on Louis Wain’s life story is The Man Who Drew Cats by Rodney Dale, here on Amazon.

If the pricing on Amazon is exorbitant (for some reason, at the time of writing, it is), get it here directly from the publisher Chris Beetles for under US$ 70 plus worldwide shipping. There is a cheaper paperback version as well but we feel that hardcover is the only way to go this one, and well worth the extra cost. Stay tuned for our detailed review in a few months time.

Chris Beetles is one of the world’s leading authorities on Louis Wain. His gallery has featured many Louis Wain exhibitions in the past and you can purchase directly from his website here without the risk of getting a forgery (of which there are many today).

We will also follow-up with a selection of Wain’s artworks that were sold at auction these past few years, so stay tuned!

*Our website is 100% reader supported and this article may contain affiliate links at no cost to the purchaser. Please peruse our About page for more details. Prices are correct at the time of writing and may vary depending on your country.

One Comment

Comments are closed.